This is why you should turn off CNBC, stop listening to Jim Cramer, and unsubscribe from Money Magazine. If you’re short on time, scroll down to the graphs, and you’ll see why Mr. Mackintosh from the Wall Street Journal could repost this story every year.

Enjoy,

John & Bill

Wall Street’s 2017 Market Predictions: Pathetically Wrong

Forecasting is difficult, but this year showed exactly how pointless it can be: Markets performed opposite of virtually all predictions

By

James Mackintosh

Nov. 23, 2017 4:58 p.m. ET

We all like to remember our successes and forget our failures, and finance is no different. As investors’ inboxes once again become clogged with annual outlooks from Wall Street’s scribblers, there is little admission of the nearly universal failure to predict what happened this year—even though the things the analysts missed are much more interesting than their forecasts.

There are two big lessons to learn from the mistakes of the year-end crystal-ball gazing. The first is that when everyone agrees that prices can only go in one direction, it is dangerous. The second is more nuanced: We really know an awful lot less about how the economy works than we thought.

Last year almost everyone was bullish about the prospects for the “reflation trade” of higher bond yields, stock prices and the dollar, driven by rising wages and Donald Trump’s tax-cut plans.

A year on and inflation hasn’t materialized, the tax discussion is bogged down in Congress, and almost every analyst was wrong. Benchmark 10-year Treasury yields are down, not up, the dollar is down, not up, and the S&P 500 has delivered more than double the gains of even the most bullish Wall Street prognosticators.

Strategists mostly shrug their shoulders and move on to their 2018 predictions. Their forecasts out so far suggest the stock rally will continue and bond yields finally start to rise, if a bit less than they thought before.

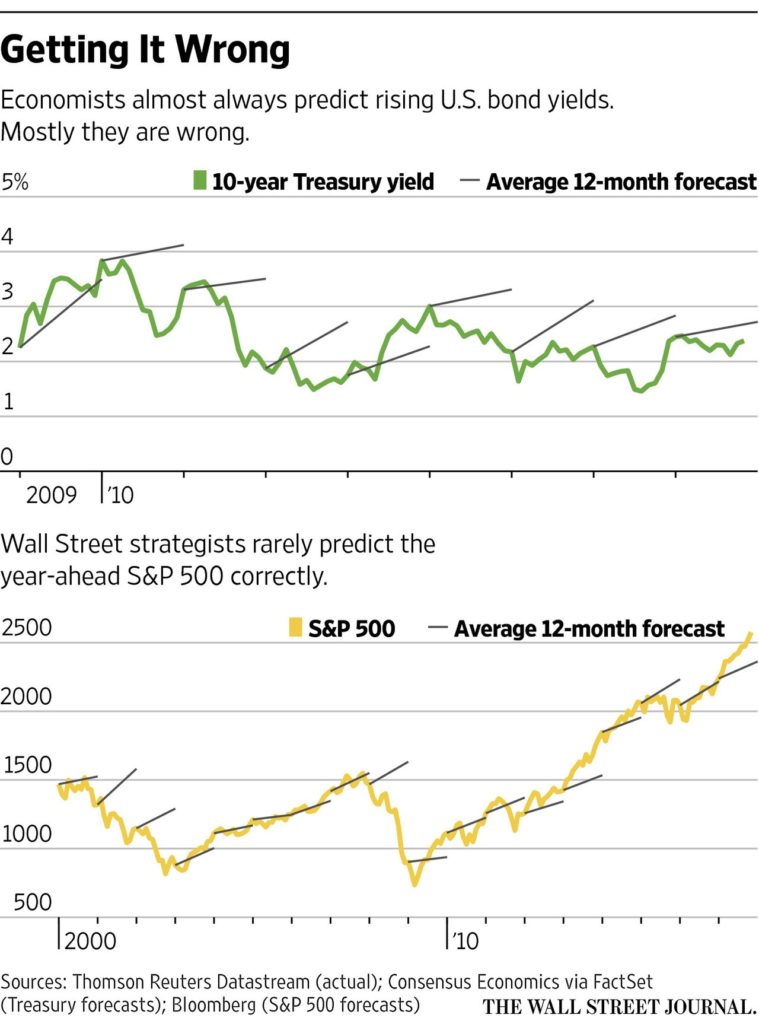

Cynics will look at what happened in the past and wonder why anyone bothers. Predictions have a dire track record, and have been sadly predictable themselves. Treasury yields have been forecast to rise every year for the past decade, according to forecasts collected by Consensus Economics, yet they have gone down more often than not. Even when they went up, the moves were only once anywhere near what was predicted, back in 2009. Forget using a dartboard to plan investments; on average a coin toss would be better.

The same goes for stock prices. Only rarely is the average S&P 500 forecast of strategists anywhere near the actual result. More than half the time since 2000 the miss has been either too high or too low by an amount bigger than the S&P’s 9% long-run annual gain.

Don’t blame Wall Street for getting it wrong, though. When markets work, they incorporate an average prediction already, so forecasting markets involves assessing when the average prediction will change, as well as fundamentals such as the economy. Both are pretty unpredictable.

“It’s doubly silly,” says M&G fund manager Eric Lonergan. “You can’t predict what’s going to happen [with events] and even if you are fortuitous enough to be right, it doesn’t help you when you’re investing.”

This year has been a classic example. Analysts thought stocks would do well as Mr. Trump cut taxes and inflation picked up, while many also predicted more volatility because of the political and geopolitical uncertainty. They were wrong, at least so far, about taxes and inflation, but stocks went up anyway. They were right about political and geopolitical uncertainty, but volatility failed to appear.

The key to what went wrong for the forecasters this year was the lack of inflation, something Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen has described as a “mystery.” As the year went on, investors became increasingly convinced that inflation would stay dormant, bringing down long-term bond yields and the dollar even as decent economic growth boosted profits and stock prices.

Like many others, Alan Ruskin, Deutsche Bank’s global co-head of FX research, started the year recommending investors bet on “the American dream” via a stronger dollar. He says one mistake was not factoring in that everyone was betting on Mr. Trump’s policies. The widespread consensus created an outsize risk of being wrong when the policies weren’t implemented.

Mr. Ruskin draws an interesting lesson from the failure of bond yields to pick up this year. Yields were held down by the $4-trillion pile of bonds held by the Fed, he reckons—in other words, it matters more how much the Fed holds than how much it buys or sells. Central banks have been saying for years that their bond-buying works by the size of their holding, not the flow, but investors have tended to focus on flow.

Not many of the year-ahead treatises have landed yet, but those that have almost all, once again, predict bond yields rising over the next year along with stock prices. It is tempting to regard that forecast as a contrarian indicator and bet on the opposite. But while that approach would have worked for bonds and the dollar this year, it would have meant missing out on a stunning share-price rally.

Strong consensus is a warning sign worth watching for. But the value in Wall Street’s year-end publications comes from the analysis they contain, not the prices they predict.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/wall-streets-2017-market-predictions-pathetically-wrong-1511474337